"A More Perfect Union" - PART TWO

/One of us is pleased.

PART 2: WHAT I DID THERE

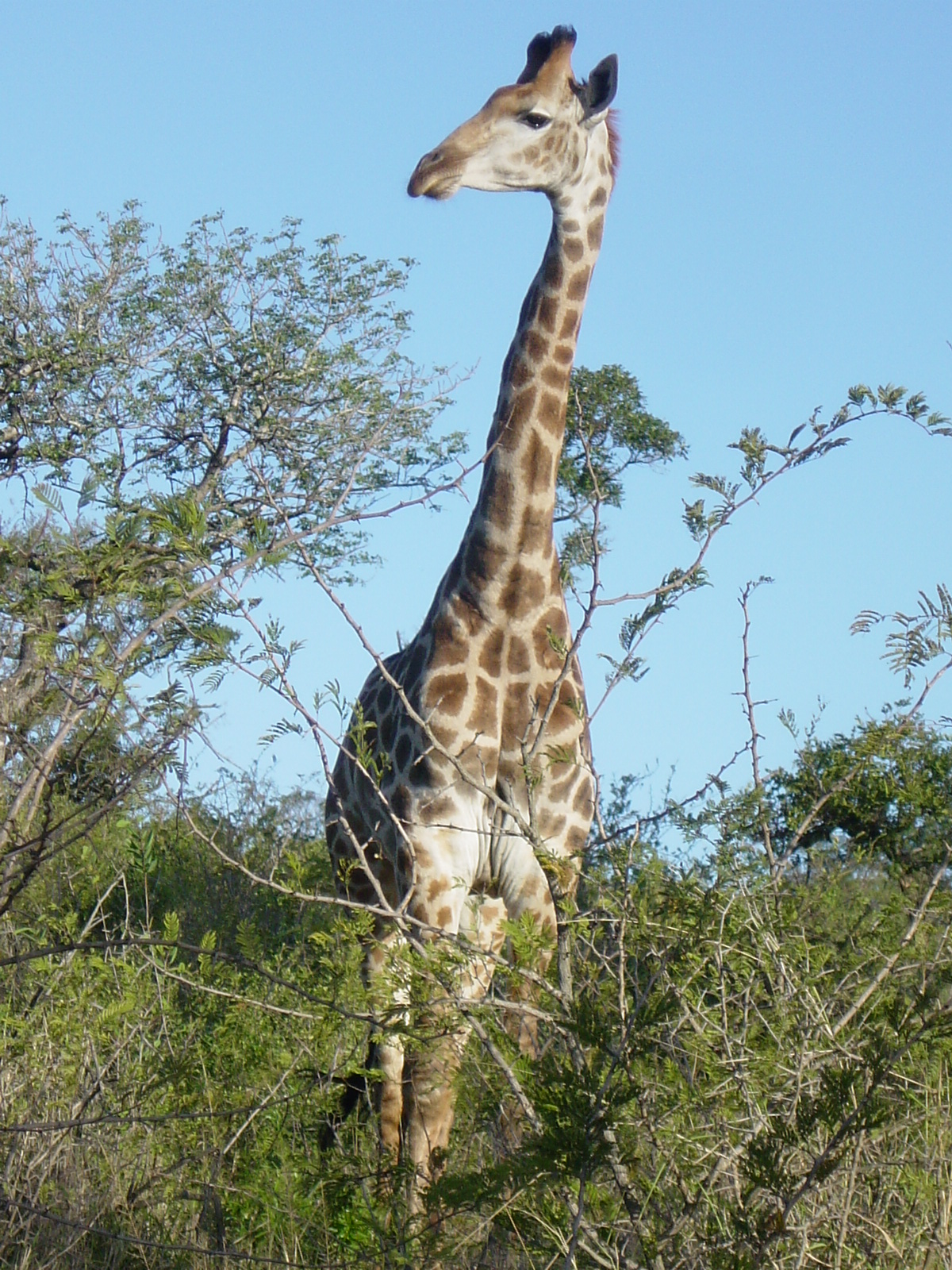

South Africa ended up being the perfect antidote to my wanderlust because it was unlike anything I’d ever seen. Of course, I was keen to see the animals. Turns out there was a small game reserve close to the office! My colleagues gave me directions there as if describing the nearest Walmart. One afternoon, another volunteer and I took my trusty little rental car for a spin in the reserve, where I fell in love with giraffes, decided I hated warthogs, and got chased by an ornery elephant. It was thrilling.

I also discovered that the east coast of South Africa is a landscape of immense beauty. The coast of the Indian Ocean is a stretch of sandy beach frequented by surprisingly few people, with a jagged coastline that wanders into the distance until it turns into the legendary beaches of Mozambique. Sometimes you could see pods of dolphins jumping in the sparkling ocean. Landward, nature was beautiful too. The highways leading out from Durban wound around gently rolling green hills; I remember the sun staining them with fresh color as I drove in the early mornings.

Being winter, the water was cold but still spectacular.

In terms of food, there is no single South African cuisine, but there are some signature eats. Chief among these is bunny chow, curry served in a carved-out loaf of white-bread, a dish that originated in Durban’s Indian population. There were only a few restaurants in the rural town where we were based, and Nando’s Chicken, with its delicious peri peri chicken, was our choice for eating out. It is still the only restaurant I associate with that town, so when I came across a Nando's in Baltimore, I knew that Kyrie Irving was right and that the world really is flat.

Bunny chow!

The most interesting discovery, of course, were the people. The Zulu people were lively and warm, and their culture was both fascinating and paradoxical to me. Here were people who had Rihanna ring tones but observed tribal traditions, prayed Christian prayers but talked seriously about witch doctors and spells. Their language seemed impossible with its clicks, but English was commonly spoken. I saw people wear traditional tribal and modern dress side by side. Some didn’t know how to work a camera, but the cell signal in the game reserve was better than in parts of the Juilliard building.

The disparity between modern and traditional, between developed and rural, was more striking than anything I’d ever seen. The interstate highways in South Africa, for instance, are really quite good. The Zulu roads, by contrast, are nothing more than battened-down dirt. To get to the rural schools, I literally off-roaded (my poor little rental car): I had to turn off the paved highway at a certain opening in the guardrails. It wasn’t marked; you just had to remember that it was roughly so many minutes after the last junction and opposite a certain field with a certain kind of tree in it. From that point on, there were no signs; there was only your spatial memory and your desire not to hit anything that guided you along the shanty houses, people, and livestock. I miraculously found one school after having been taken there once or twice, hoping the entire drive that my mental map would hold. This was ten years ago. No one used GPS. The first iPhone had just been released to the world. I really don’t know what I would have done if I had gotten horribly lost.

Found it! Phew! View of the "parking lot."

The influence of the tribal culture was totally new to me, as an outsider, but I could tell it was vitally important. My first day in the field, I went along to a meeting with the local inkosi, or tribal chief. As far as I could tell, the chief had no official governmental power but was a cultural figurehead, at the level of a religious leader. He seemed to have considerable sway in all matters and was a source of authority I had to consider in my research. A tribal chief! I felt like I was at Epcot Center at Disneyworld, that’s how much I knew about this sort of thing.

When I wasn’t in meetings and activities with the staff, I worked on my research. The legislative and policy research was pretty standard, as was the scientific and medical research on HIV/AIDS. The way more interesting part was when I tried to understand how all of this information impacted rural schools. That meant interviewing teachers, administrators, students, and other constituents to ask them how they felt about this or that. I must have been a sight, an Asian girl with an American accent wearing borrowed clothes (in Zulu culture, women wear long skirts for proper occasions and I didn’t bring any) asking a very conservative group of elders how they felt about condoms in classrooms. I had some people tell me that only I, being such a strange sight, could have gotten away with asking the questions I did.

One of our "parent" meetings.

----

When you’re as far out of your comfort zone as I was, you’re bound to learn some life lessons. Here’s one I learned: you cannot hear what someone is saying until you understand their context. As intimidating as it was to ask the questions, listening to the answers was even harder because they changed based on the context of our meetings! For example, in my largest community meetings, the pattern was that mostly men would stand up to mostly denounce AIDS prevention efforts in schools on the grounds of protecting “tradition.” However, as the groups grew smaller, I heard different things - I heard support for anything that could stop the epidemic. I heard openness to measures like more thorough sexual education. I heard teachers' and administrators’ frustration at their daily struggles with the fallout. Above all, I heard (and felt) an exhaustion at the disease’s toll. People were worn out by the deaths of young people and constant funerals. In personal conversations, both men and women said that something had to be done and that new measures, such as the ones we were proposing, had to be considered.

The reason the consensus differed so much from public to private arenas was clear - traditional values made it very, very difficult to have frank discourse about sexual health. Schools did not teach sex education, nor did parents, so any information came from peers, which usually included a host of dangerous myths. Matters of sex were more likely to be ritualized, rather than discussed - For instance, I had read about virginity testing - a ritual where young girls are deemed pure or not by genital inspection in a public ceremony - but assumed it was a figment of the past. A staff member corrected me and affirmed to my shock that it was very much a current practice. Given the cultural symbolism of virginity, it was small wonder that talking about it in schools might be viewed as a threat to traditional values.

To make matters worse, one key constituency, parents of these school-age children, was hard to find. When I scheduled a parents meeting at a rural school, I saw in the packed crowd mostly older women and men, grandmas and grandpas. They were the caretakers of the students now -- the in-between generation was gone. AIDS had left behind the age demographic most rooted in the tribal tradition to handle its aftermath (this is apparently still true).

Although the schoolchildren were wonderfully responsive, the influence of their culture was heavy in everything they said. I gathered that HIV/AIDS had become a taboo word - many raised their hands when we asked who had lost their parents, but when I asked how, they said pneumonia. Not a single one said AIDS or HIV. Since it was likely that many of these kids themselves were infected, it was astounding to me that the greatest influence on their well-being remained an unspoken entity. How do you discuss something that cannot be named aloud?

These conversations taught me another remarkable truth about my fellow man - that people will die before they betray their society’s beliefs. For the most traditional of the Zulu people, not so removed from their tribal history, candid discourse about a sexually transmitted disease could be more difficult than death. I heard stories of adults who had been diagnosed with HIV/AIDS who denied the disease and available treatment, though they must have known what was happening. When they got sicker, the things that had already happened to others around them happened to them, and the inevitable came to pass. The knowledge of science and the availability of antiretroviral therapies were powerless in the face of culturally imposed silence.

People will die before they betray their society’s beliefs. That was what the public health community was up against. I could propose solutions until the cows came home, but unless people felt heard and their values taken into consideration, nothing would work. Ultimately, it was the ideas and recommendations of students and teachers’ that were the most promising, sensitive as they were to the cultural pressures around them.

Perhaps the biggest lesson I learned was that humans really are the same everywhere on earth. It’s not a far cry from rural KwaZulu-Natal to America today. It’s been often said since the election that certain Americans are acting against their self-interests. I find this completely untrue. In my experience, people always act in their own interests - if you don’t understand how they act, then you don’t understand their reality, period. If you don’t understand their reality, then no meaningful discussion can happen, no matter how well-informed you are. During my time in South Africa, I first thought that my value was to bring legal knowledge. Then I thought I could serve best by asking questions, but I realize now that perhaps my greatest contribution was to come into the room and listen as deeply as I could.