Why We are Mentoring All Wrong

/A line in a recent New York Times article caught my eye: “High-potential women are overmentored and undersponsored.” Intrigued, I followed the link to a Harvard Business Review feature, which mentioned a woman who felt “mentored to death.”

Yes. Nameless high-potential woman, I hear you. I'm not sure if I'm a high-potential woman, but I have grown wary of being “mentored.” It’s gotten so bad that whenever I hear about another mentoring program, I roll my eyes. Having been a minority woman in the fields of science, business and law (particularly corporate law), I’ve been in my share of mentoring programs. And I agree with the article - such programs cost time and money and have very little to show for it. In my experience, mentoring programs follow the same formula: pair me up with someone who matches me in two dimensions (usually gender, field or ethnicity), and give my mentor a small budget to take me out for meals a few times a year. It’s perfectly nice, being taken out to meals by a perfectly nice person, having perfectly nice conversations about our lives, but I can’t say I’ve benefited much beyond that. If the point of mentoring was to give me an extra boost, as a minority or woman, into the higher leadership circles of my field, it definitely hasn’t done that.

The HBR article concurs. The upshot of the study is that women do get some of the benefits of mentoring; just not the ones that really matter to advancement:

“They were not getting that sponsorship. They were getting mentoring. They were getting coaching. They were getting developmental advice. But they were not getting fought for and protected, and really put out there.”

The result was a correlation between mentoring and promotions for men but not for women, despite women having just as much (or even more) mentoring.

Why doesn't mentoring do as much for women's advancement? The study co-author, Herminia Ibarra, focused in on what she called the “sponsoring” function of mentoring. Basically, it’s when a mentor, usually a higher-up, uses their position to go to bat for you, to advocate for you, to protect you and defend you in the fights that matter. For some reason, many mentors - program-matched or organically grown - just don’t do that for women.

This got me thinking about the mentors I’ve been lucky enough to have. Even in music, where advancement and promotion are not as defined, there are people putting themselves out there for me: advocating for me, recommending me for jobs, supporting my proposals for change in the face of resistant systems. These people exist, and for them I’m very grateful.

I want to tell you about one of my first musical mentors (an unlikely one at that) and what I learned about true mentorship. The year was 2008, and I had just arrived at the Manhattan School of Music on a bit of a crazy lark: I had finished law school, accepted a full-time law firm offer -- and decided to first take a break to play piano. During the doldrums that are the 3L year, I dusted off my fingers, took a few lessons, and auditioned for piano graduate programs in New York and London. MSM gave me the most scholarship, and not knowing any better, off I went for a year of piano-cation.

Upon arriving, I sought out performance opportunities; turns out, this is no easy task! Through the grapevine, I heard that this one professor held a performance class every Tuesday for two hours where anyone could play anything and he would give you comments. Sounded good to me!

I went to visit the class one week. It was held in a beautiful recital hall, and students who had signed up would queue up to go on stage and play through their piece for the professor, who sat in the audience. I can’t remember the exact moment I first saw David Dubal, but I remember it was a bit of a shock. Here was a man dressed famously in a head-to-toe purple velour (velvet?) suit plus a colorful scarf or old-fashioned hat, with long and quite unkempt gray hair, dark sharp eyes, and a strangely loud and reedy voice. His appearance was odd, but his comments were completely screwball. He made up nicknames for students on the spot (my favorite one was “Juliana Liebestraum” but often I was “the Han woman”). He described music in the most colorful ways I had ever heard. I recall him once describing at length a particular brand of jarred olives, to describe the briny smoothness he wanted out of a student’s sound. “This is the oracle?” I thought to myself. “What an odd dude.”

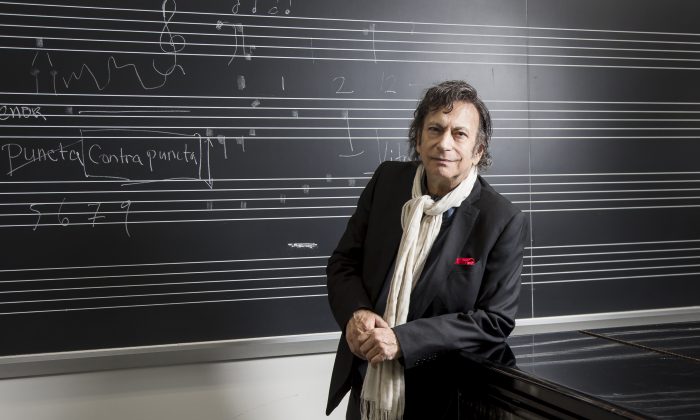

Dubal in his element.

It took me weeks to muster up the courage to play in front of him and the other impressively talented students (I hadn’t played for so long!), but once I started, I played in his class as much as I could. And after a while, I understood not only his greatness, but his critical value to my musical development. Without overstatement, David Dubal has been one of the most important people keeping me playing the piano and helping me progress in my artistry. In that sense, he has been one of my most important musical mentors.

It’s difficult to encapsulate someone who means so much to you, but I’d like to share four features of a true mentor and how Dubal embodied them to me.

ONE: A mentor knows the field. Cold.

There is no doubt that Dubal is an authority when it comes to the piano. He’s written multiple books, including The Art of the Piano, an encyclopedic must-read reference about piano's performers, literature and recordings. He’s hosted radio shows about the piano for decades. He’s given lectures everywhere. The man knows the piano better than just about anyone.

So when you perform a piece for him, he has all of the context: the composer’s trajectory, the style, the seminal recordings of the piece (he knows what year they were recorded and, uncannily, their exact timings). This context gives him a musical intuition that is not just thoughtful but utterly informed. If he says the tempo or pacing is off, or the texture too thick, or you’re not following the markings, it’s not because he doesn’t like it, but because the weight of the classical music tradition says so.

I’ve come to trust his ears. If he hears something that can be improved, it’s worth considering. He may not always tell me how to fix it, but I trust that his comments are in good style and taste. And what is style and taste in art if not gleaned from context?

TWO: A mentor knows the challenges you’re facing.

In those MSM years, I faced the tough reality of trying to play difficult music despite a lack of training and years of disuse. I no longer was a fearless kid, performing concerti in front of hundreds of people with nonchalance. I was an adult who was acutely aware of my shortcomings. I face-planted on stage ALL THE TIME. My hands would get sweaty and I’d slip off the keys. My heart started racing the minute I approached the stage. My memory would freak out and I couldn’t finish the piece. These trials by fire were devastating, yet I made myself do it repeatedly because I knew I had to. After one class, I crept out of the class, slumped down in a nearby hallway and quietly cried out of shame for about half an hour.

Piano is hard. Performance is even harder. And Dubal knows it. He’ll be the first to point out how tricky a deceptively simple piece can be, or how much bravery it takes to go on stage and put your skills on display. That day I utterly crashed and burned on a Chopin scherzo and went out into the hallway to cry, he had gently advised me not to worry, that it just needed a lot more time, and that I should hole up in a practice room for a week to get it right, and that he'd send roast beef sandwiches to my room every once in a while to keep me going. When anyone (many of us) showed signs of nerves, he was gentle but realistic. I remember him saying, “playing the piano is the hardest thing there is,” and I believed him. He told stories of famous pianists who were debilitated by stage fright, including Vladimir Horowitz, whom Dubal interviewed extensively. He had plenty of advice for the challenges, often instructing us to play through our pieces multiple times to feel how the second and third chances felt less pressured. Then, he would remind us to play as if it were already a second chance, or to remember that our lives were long, and that this might just be the third performance out of hundreds. These days, I don’t get debilitating nerves anymore, but if I'm a little too jittery for my liking, I think back to those words.

THREE: A mentor gets what you’re trying to do.

After MSM, I went to Cravath for a few years, only to (unexpectedly) return to music at Juilliard. Luckily, Dubal was there too. There, he teaches the most popular adult-division class for decades running, “The World of the Piano.” This too is a forum in which pianists can run repertoire, alongside commentary by Dubal about the music and the composer.

I can’t stress how valuable it is for a pianist when preparing for a public performance to have adequate practice runs before the big date. Dubal’s class is one of the few reliable options I have, and to that extent it is a huge resource. He tries to accommodate everyone who needs time, welcoming alumni and students and random guests alike.

The Juilliard class. More photos and recent article about Dubal here.

He often introduces us and our stories to the students in the class, most of whom are working or retired adults who are all passionate about music, but not necessarily pianists themselves. One day, while describing us pianists, he was enumerating the various challenges we face today - low income and lack of jobs, long hours and low appreciation, declining audiences, poor music education in the population - and said that pianists struggle against all odds because, above all, “they just want a place to play.” In that moment, I knew it was true. We performers just want a place to share our art with people. That, above money or fame or recognition, is what keeps us going. That’s why playing for myself in my apartment after a "day job" will never satisfy me.

Many times, his offhand commentary about a musician’s life just rings completely true. About practicing, he once said that he has to do it everyday, otherwise he feels as if he hasn’t brushed his teeth. I have yet to find a better way to describe the compulsion I feel to practice, and the discomfort I feel when I can't. As a lifelong pianist and lover of the piano, Dubal gets us and what we’re trying to do.

FOUR: A mentor knows what support you need, even if you don’t.

Observing Dubal in those MSM classes, I realized that his feedback was quite uneven - he’d tear into the details of the score for one student who seemed quite well prepared, but heap praise on another student who I felt had barely gotten through her piece. I realized over time that he gave each student just what they needed at that point - whether it was encouragement, a few key points, or a barrage of details. For me, on my lowest day, he could have torn my disastrous Chopin scherzo apart and handed down any number of scathing criticisms I was already heaping on myself -- but he offered roast beef sandwiches instead. I remember one girl who came in and said that she was discouraged in her piano playing, but then proceeded to play one of the most passionate renditions of a Bach prelude and fugue I have ever heard. It wasn’t perfect, but it had so much verve and rhythmic power, and here was someone who was considering quitting the piano. Dubal told her loudly enough so that everyone could hear, “LISTEN TO ME. You must keep playing. The world needs to hear this.”

I’m not sure how he knew what we needed; he just did. After graduating MSM, I started work at the law firm. I thought that I’d find rainbows, a pot of gold, and happily ever after at the firm, but within months, I knew that wasn’t the case. It was a busy time for M&A in a busy M&A group in a busy law firm, and the first few months went by in a blur of far too many deals at the same time.

As the most junior lawyers, we had been informed that we shouldn’t expect to go home for Christmas. So I didn’t make travel plans, and good thing, because there was a huge push for a deadline on December 23rd. I remember working late into the night with Christmas music in my office, singing along and skipping through the halls with delirium to my mid-level associate’s office. There was something sad about not being with my family for Christmas for the first time in my entire life, but I tried not to let it get to me.

And then, out of the blue, Dubal called and left a voicemail on my phone. This is what I remember of it: “Juliana, I haven’t seen you for a while. I fear you have been consumed by some …. Work or JOB (<disgust in his voice>). Always remember that you MUST play the piano, you must ALWAYS play the piano...” I sat in my office, my office chair like a ship adrift in a paper ocean, completely unmoored. Play the piano? Me? Now?

It took another year for me to decide to return to music, perhaps for the very first time. That voicemail is one of the most meaningful and touching gestures I have ever received - from someone who believed in me when I had given up on myself, from someone who saw my passion when I hadn’t yet found it, from someone who knew the path and the darks and lights and was willing to help me through it. From someone who knew the challenges of the journey all too well, and yet knew that the struggle was a worthy reason to attempt it.

I don’t know if these institutional mentorship programs will ever get it right, because to be a true mentor you have to have the passion for the field, the wisdom and intelligence to grasp the problems and the solutions, and rarest of all, the empathy for those rising through it to help any way you can. It’s a tall order. But if you have those things, you really can change someone’s world. I’m grateful for Dubal, and for my past and future mentors on this life path. Free meals are nice, but I’ll take a roast beef sandwich from a mentor any day.

Chopin-approved.